HEMP talks with the renowned activist about her efforts to bring hemp back to the forefront on Native lands, build a post-petroleum economy, and more.

This article was originally published in Issue 7 of HEMP in August 2019. Subscribe HERE or find in a local grocery store.

Now is the time for doing, not the time for talking about doing, Winona LaDuke tells me as she drives across South Dakota. The perceived irony of speaking such a statement out loud is not lost on her, nor is the realization that one can multitask: LaDuke is exceptionally good at both talking and doing.

The activist, author, farmer, and two-time vice presidential candidate for the Green Party has spent her decades-long career focused on raising awareness for various causes while trying to implement the solutions she’s fighting for. She helped found the Indigenous Women’s Network in 1985 to support Native women. She founded the White Earth Land Recovery Project in 1989 to buy back land within the White Earth reservation from non-Natives, while restoring traditional food practices. In 1993, she co-founded the Honor the Earth non-profit to raise awareness and funds for Native environmental issues. And she was a water protector at the Standing Rock Dakota Access Pipeline protests in 2016 and 2017, frequently giving interviews to national media outlets about the fight for sovereignty and against fossil fuels.

In essence, LaDuke can walk the walk — but she’s also one of the people who first presented the ideas that everyone else starts talking about before they walk. Right now, LaDuke is working on the creation of a new post-petroleum economy. And she sees hemp as front-and-center in that necessary future.

When I spoke with her this spring, LaDuke had already started planting hemp on her farm, alongside a series of other crops, using only horse and human power. Hemp is so important for the post-petroleum economy, LaDuke says, because of its potential to create products like hemp plastic, hempcrete, and hemp textiles that can replace petroleum-based products.

And she’s adamant that Native voices should lead the new post-petroleum economy, which includes the hemp industry. “People should back up,” she says. “We know the right things to do for hemp and that’s what justice looks like.”

HEMP: So, what are you working on now, as you drive through South Dakota?

Winona LaDuke: Well, my original plan for today was to speak about hemp in Washington, D.C., but I cancelled going to D.C. It was a nice idea, but I’m in a situation where I can talk about it or I can do it. And right now, I had to do something and not talk about doing something. It’s maple syrup-ing time. My son is harvesting maple syrup for his first time on his own and I wanted to encourage him. Also, I wanted him to do cool. There are a lot of young men out there and we’re trying to encourage them to do cool things.

We also wanted to have time to start some of our hemp plants on our farm. It was just the full moon, and you want to plant during the full moon, so we planted a bunch of CBD hemp this past weekend. We also planted all of our tobacco plants and a bunch of other seeds, because, you know, we grow a lot of plants, not just hemp.

Also, I want to be home and be a part of my family’s life. My family misses me when I’m on the road all of the time.

Winona LaDuke’s family harvests hemp on her farm in northern Minnesota.

This is your fourth year growing hemp. How has it been so far and what have you learned along the way about growing hemp compared to other crops?

I’m mostly growing a seed and fiber variety of hemp. I’ve always been interested in fiber because I want to change the textile industry. Right now, the textile industry is so ecologically destructive. I’ve been committed to hemp fiber, and of course, I want to eat the seeds from those fiber plants, too.

In our first year, we had seven hemp growers on the reservation. Now, there’s like 45 and it’s wide open. In the first year, we put in that crop and we started looking around and trying to understand the soils. Then, I inherited the tribal hemp crop, and that is my next challenge. That hemp crop has perennialized and is the happiest crop on the planet.

Perennialized, really? That’s unusual. What it’s like having a perennialized hemp crop, instead of the standard annual crop that’s harvested every fall?

Well, this hemp is for fiber, not for CBD. One of my concerns is that I want not to treat the plant like a slave. The plant needs to be able to reproduce and it has a right to reproduce. When you have fiber hemp, perennializing it means you are less impactful on the soil and you can sequester more carbon by leaving it in the ground longer.

Have you noticed the soil getting healthier through perennializing the crop?

I think it is. I’m trying to understand it more scientifically. I have some theories and I want to do some more research and really pay attention and start documenting the plants’ wellbeing.

You know, the fiber industry is not about competition, it’s about cooperation. We’re going to need people to grow a lot — a lot — of hemp to change the textile industry in this country. Everyone wants to figure out how to make a lot of money on CBD, but I’m trying to figure out how to protect Mother Earth, protect our water, protect our soil. I want to learn how to grow different varieties, how to process them… it’s super interesting.

Why do you think it’s important the hemp industry cooperate to grow more hemp?

If hemp can help build soil and sequester carbon, that’s a pretty big thing to be able to do. But also, take for example my home state of Minnesota. Almost everyone has a boat in Minnesota. If we’re going to move to a post-petroleum economy, you’re going to need a whole lot of hemp to get those boats made from hemp plastic instead of regular plastic. That’s not boutique production. We’re not making doilies here.

Winona LaDuke holds decorticated hemp that can be used to make hemp fiber products.

Let’s talk more about what you mean when you say the “post-petroleum economy.” You’ve written about how your people, the Anishinaabe people, have a prophecy that “a time will come to choose between two paths, one scorched and one green.” You’ve said the green path means post-petroleum. What do you think we need to do as a society to get there?

I could say that we should get our heads out of our asses. That would be super helpful [laughs].

I can also say that we should just get out of our box. People live in this created world now that exists in one box or another: a cell phone, a car, a house or apartment. We need to be in a bigger picture.

We need to change the transportation system so that it’s not based on rubber on the road. We have to have electric rail. We need to grow organic. We need a hemp economy that is at scale and supporting the ecosystem and the world. We need to get off petroleum plastic, because if you’re going to get off fossil fuels, you need to get off plastics. It’s not too hard, really. There’s like a gazillion ways to do the right thing.

So you’re saying it’s important for us to leave the box, not just stay in the box and paint it green.

Absolutely. I absolutely believe that you have to think systemically. This climate crisis is not an individual problem. It’s not about how I individually am working. It’s about how the system is set up. There’s a lot we can do to achieve the new future, and we have to be the collective.

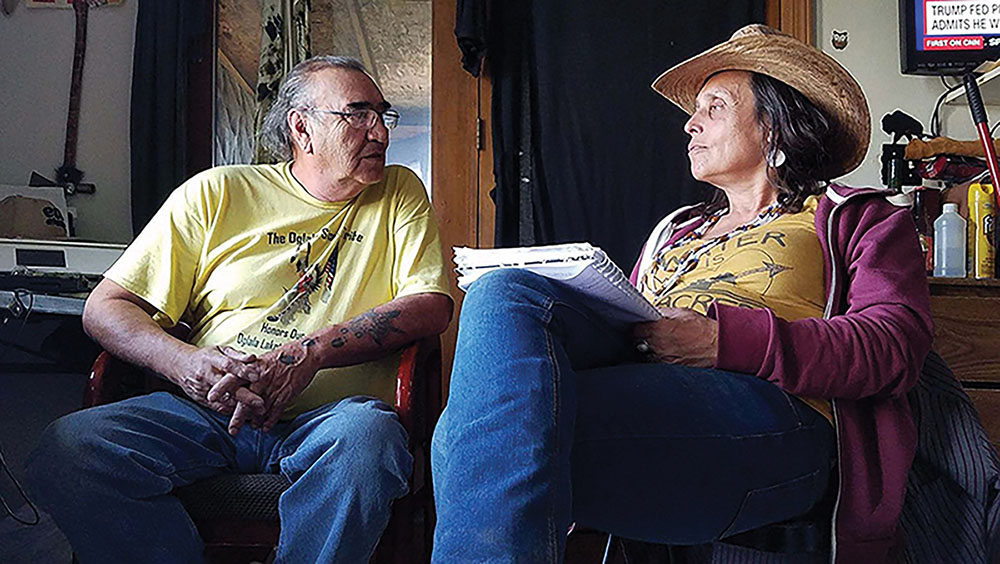

I’m out here in South Dakota. I’m about to give a speech and put on a dress and get on stage and then I’m going to go out to Pine Ridge and see some relatives and have some prayers and talk to their tribal council about hemp. That’s because people are interested in change. People want to do something that will build the next economy.

The Native people have been working on hemp for a long time. Particularly the White Plume family has some blood in this. I’m interested to see how Native people can be at the forefront of the textile hemp economy, and the CBD economy if we’d like as well. We do good for this plant and we have a lot of land. No one else has the kind of land that we have.

Winona LaDuke talks with Alex White Plume, former president of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, who first planted hemp 20 years ago.

Massive corporations might have enough land to compete, but you’ve made clear you don’t want them at the forefront.

The hemp economy needs to be led by people who look like you and me. The mess we’re in was created by a bunch of rich white dudes, either in corporations or in the government. They’ve had their shot and they’ve done poorly. So why would we let them lead the next economy? I’m like, no, thank you, we’re okay!

It’s our plan now to build a hemp textile mill. Right now, I’m wandering around the country and the world and looking at hemp equipment that can be built in a way that is good for communities and good for the environment. I’m really interested in that. But right now, there’s a lot of questions and not too many answers.

Tell us more about your plan for a hemp mill in Minnesota. Are you finding the kind of quality equipment you’re looking for to build the mill?

Let me be clear: I don’t know a lot about textiles, but my grandmother was in the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, so perhaps it’s in my blood.

Unfortunately, the hemp mills in the USA were decommissioned in the 1940s, which was the last time hemp rope was made in Minnesota. There’s not a lot of knowledge remaining about the technology, so it’s like being a detective trying to figure it out now. We’re looking at milling equipment internationally and we’re looking for people who would want to talk with us about it. We’re doing a lot due diligence, and we’re hopeful that we can build a mill by importing the equipment and working with it in our communities.

“We should just get out of our box. People live in this created world now that exists in one box or another: a cell phone, a car, a house or apartment. We need to be in a bigger picture.” — Winona LaDuke

One of the last hemp mills was in Winona, Minnesota. Do you think that’s a coincidence?

Nope, I think it’s divine intervention [laughs]. Not really — I’m saying it’s divine intervention and laughing. But, in some ways because of this, I do feel responsible to bring hemp production back to Minnesota. The last hemp mill was in Winona, Minnesota, so it’s on me. I’m about to turn 60, and I’m going to have a party in Winona, Minnesota. I’m about to go to Pine Ridge and sniff around for some more Winonas to invite to the party. Winona, in Indian country, is a name sort of like Joshua. It’s not so unusual. I think when you turn 60 you should have the ability to do something fabulous. When I’m 60, I’m trying to build a hemp economy [laughs].

I’d love to talk about the horses on your farm and how it has been growing hemp with horsepower.

I have a partner named Chuck who has been working with the horses. He did an inaugural run with the horses. At first, I felt like I was on a chariot riding the horse-powered plow. It’s super fun. I’m looking forward to farming. We’ll have three teams of horses this year we think, which is unheard of. We have three different sizes of horse: small, medium, large. You have to have the right horse. For example, on a small field, we might use a pony. At some point, you might want to use four big workhorses. It’s going to be fun and I have no idea how it’s all going to happen, but it’s starting to emerge. I have put in hemp with the horses. I do have a seed drill that can also do that, but I’m trying not to use it. I’m interested in the post-petroleum economy, so I’m trying to do it all without the help of fuel.

It seems like quite the challenge to farm at scale without petroleum.

You have to think about the Amish. The thing is, what I’m interested is this question about scale. Because the more energy it takes, the more likely you are to need fossil fuels. So what is the scale where you don’t need fossil fuels? At what level are you at where you’re just one step away from needing fossil fuels?

If you’re trying to feed more people — we have a lot of people — you’re going to need a lot of effort, but of course, we could have more people working on growing crops. I’m also thinking about this question of scale when I’m thinking about the mill. How could we have the mill run on wind power? There’s Class IV wind in Minnesota.

Do you think you’ll be able to build a wind-powered hemp textile mill?

We use the term “windmill” because wind used to power grain mills, and the wind can power a mill, we know that. So can water. But this is where my skill set begins to diminish because I’m not an engineer. It is quite possible. I’m just saying, you can recall from history that we have been able to use wind, water, and horses. We’ve done it before without petroleum and we can do it again.

I read your book “Recovering the Sacred,” which discusses the ways governments and corporations have interrupted sacred Native practices by controlling land and resources. I was wondering if there are any stories you’ve heard of similar to the stories in that book, about the ways government and corporate projects are impacting land to cultivate hemp?

I’ll give you an example. My village, aside from the fact that we’re facing the largest pipeline company in the world, which messes with the water in our neck of the woods, has a problem. My whole village of Pine Point is surrounded by industrial potato farmers. There aren’t too many people growing hemp out there except us, but when those potato guys are spraying pesticides, it’s like, go to hell.

For decades, you’ve been doing work on the White Earth reservation with heritage seeds, now through your work with the Anishinaabe Agricultural Institute. Why do you think it’s important to be restoring heritage seeds?

When I was an undergraduate at Harvard, my father came to see me one day. He was an old-school Indian guy and he said, “You’re real smart, but I don’t want to hear your voice if you can’t grow corn.” This was in 1980 that my dad said that to me. So I’ve been growing corn since about 1990, and I’ve been growing heritage varieties. I grow corn, beans, squash, Jerusalem artichokes, tobacco, traditional potato varieties, hazelnuts, and then I grow CBD and fiber hemp. I grow a full variety of products and of things, but a lot of our seeds, there wasn’t that many of them left. Our corn varieties are really intelligent and they are adaptable for many weather conditions. I’m a firm believer in agrobiodiversity. It’s what you want if you want humans to hang out on this planet for another 500,000 years. We’re going to want agrobiodiversity if you want those things.

“Tribes are ready to roll. What we need are a lot of people to support us.” — Winona LaDuke

So you’re working on preserving those genetics?

Yes, by growing them, but also by feeding the harvest to other people and encouraging other people to grow them.

My hemp interest has to do with the fact that very few people know about the varieties of hemp. There’s a lot of possibility there. Native people deserve to have a research institute that reflects our values, and our values are best promoted by all of us. I want to provide hemp education about varietals, about being able to protect our plant breeds, about what kind of soil conditions promote growth, and those type of things. To some extent, I’m not sure we’re the people to lead on CBD. I want to be talking about things like hempcrete, like rope making, and learning about hemp processing. I want to grow out all of those things. I love farming; I love growing things. It makes me happy.

How much of the time are you on the road? And how much time do you get to be at home working on the farm?

Right now, let’s just say that I’m crowdsourcing for this hemp project. I’m going to speak at a bunch of universities, so I have to go speak to get the money to make my hemp projects come to light. In spring and fall, I go talk to people. In the summer, when we’re farming, I stay in my territory most of the summer. In the wintertime, I write and I’m with my animals, and I take off and find my friends in the sun. I’m super committed to the growth of hemp. I’m interested in how this is going to unfold and I want to be a part of unfolding this in a good way. I’m happy to be here.

Winona LaDuke’s farm in northern Minnesota

How are you feeling about hemp legalization so far? Are you feeling pessimistic about the rise of big corporations in the industry, and if you are, what are you doing to cope with it?

My philosophy is that these people should back up. We know the right things to do for hemp, and that’s what justice looks like. The people that were in the bottom of the last economy need to be at the front of the next economy. Tribes are ready to roll. What we need are a lot of people to support us. We need the technical support. Tribes are in a different situation. We have a right to our seeds and a right to our future.

What are the sort of actions that need to be taken right now in the hemp industry?

I just remember that the plant is not a slave. The plant is a being. Hemp is both male and female, but much of the magic is in the female plant, and we need to respect that plant. During this renaissance, we need to treat this plant as beautiful. I’m really optimistic about this moment. We want the plants to be welcomed. I want to encourage people to be positive and work together, that’s the short of it. We have to be mindful of this magical moment, and we need to think out of the box. Do not get stuck in the box. Our ancestors were guided by the stars, and today, most people need a GPS to get anywhere.

We’re going to make the Green New Deal up here. We’re going to do the “Sitting Bull Plan.” You know, Sitting Bull said many great political things, and in recognition of him and in recognition of the fire that came from Standing Rock, I like to call the Green New Deal the “Sitting Bull Plan.” He said, “Let us put our minds to see what kind of future we can make for our children.” That is indeed a profound thing to say, because that’s what it will take — we have to bring our minds together.

We have renewable energy, we have local food, we have agrobiodiversity, we’ve got water. Change is local. It is a woven net of relationships, but it has to be local. No one is going to save you in Washington, so you have to save yourself. And that’s what I’m here doing.